Starfield VI

Leveraging practice-Based Research to Advance Primary Care

Imagining Practice-Based Research Networks in this Moment of Challenge & Opportunity

Hyatt Regency – Reston Virginia

Sunday, June 16, 2024

This Year’s Summit

Dr. Barbara Starfield’s work demonstrated that countries with primary care-oriented health systems have better population health outcomes, higher quality care, greater health equity, and lower costs.

The Starfield Summit is an ongoing series of meetings that provide an opportunity for conversation among a diverse group of leaders in primary care research and policy. The Summits are intended to galvanize participants, generate important discussion, and enable research and policy agenda-setting in support of primary care function as an essential catalyst in health system reform.

Speakers:

Drs. Wilson Pace, Warren Newton, Kurt Strange, and Kevin Peterson

Activities:

Appreciative inquiry, group activity envisioned PBRNs addressing health, equity, and primary care workforce issues, small groups taking the emerging visions of PBRNs to create a design plan.

Principal Sponsor:

American Diabetes Association

Gold Sponsors:

American Board of Family Medicine and the American Academy of Family Physicians

Silver Sponsors:

NAPCRG

Partners:

Association of Departments of Family Medicine

Joseph LeMaster, MD

Wilson D. Pace, MD

On Sunday, June 16, 2024, 49 people attended the Starfield VI Summit from 34 different organizations/practices and three countries. There were seven different sponsors for the event.

Kickoff Appreciative Inquiry – Small group sharing

Why I’m not a keynote speaker: personal history, challenges, current opportunity for PBRNs (20 min)

Discovery: paired reflect & share on peak experience re PBRN impact on new knowledge for health & equity. (12 min)

Shout-out and set up of small group Dream activity (3 min)

Sharing the dream

Groups of 6-8 use posterboard, crayons, creative materials to envision, at the level of metaphor & story: PBRNs in this moment of opportunity to address, health, equity & primary care workforce

What would PBRNs look and feel like if they were about those peak experiences we just shared?

Shared ideas and research questions

Designed together with people and budget in mind. Sometimes all the people are within primary care, while other times primary care teams are collaborating with specialty care and specialty care researchers.

When successful PBRNs are more than just one individual project and greater than just one idea. They bring together many different people. In medical practices this includes clinicians, staff, nurses, administrators, patients and the community. In academics it includes investigators of all sorts.

Creating meaning (asthma study)

The “meaning” found within PBRNs came up multiple times. This is the bigger context in which a study may sit. For example, while an asthma project is important for the individual patients and practices, in the larger context the approaches to asthma in primary care research are part of state and national research efforts and possible training or policy initiatives.

When things go well (Asthma Toolkits and Community AIR project)

Involved patients, community members, practices, clinicians, schools, organizations.

Newspapers in an entire geographic region of a state.

The asthma project combined evidence and story. Over 1000 people were engaged in the rollout of the project in communities and practices. The study improved asthma treatment in practices and resulted in decreased ER and hospitalization for asthma exacerbation.

Major Themes

Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) and Health Equity:

Emphasized the role of PBRNs in addressing health equity and workforce challenges in primary care.

Discussions focused on how PBRNs can leverage their networks to improve care delivery, engage with communities, and foster equitable health outcomes.

The concept of “bridges” was highlighted as a metaphor for connecting research with clinical practice, communities, and various stakeholders.

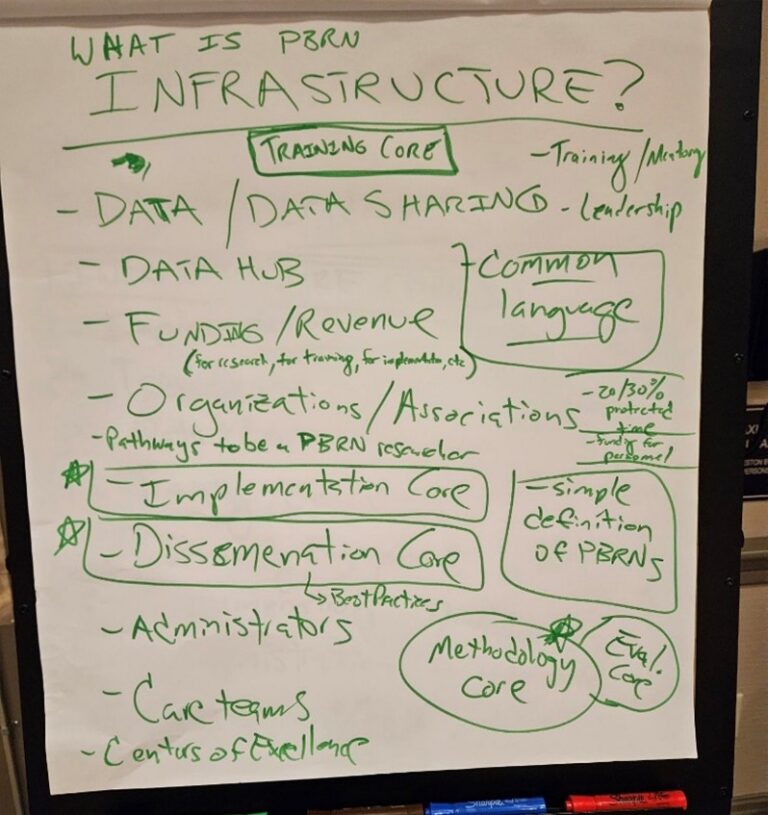

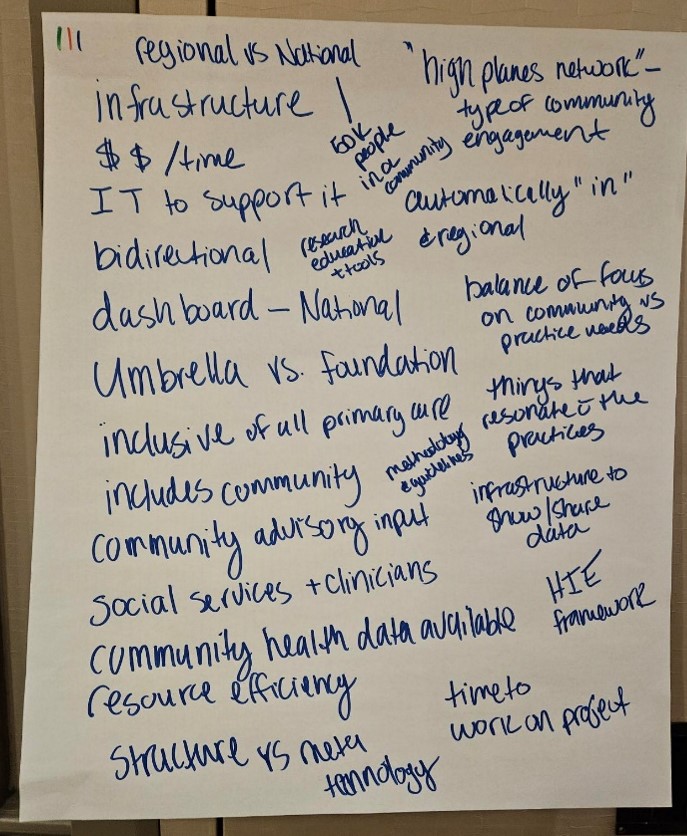

Infrastructure and Collaboration:

The need for robust infrastructure was a recurring theme, including the creation of Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Research.

Emphasis on building partnerships, leveraging existing infrastructures, and ensuring the sustainability of research initiatives through diversified funding and strategic collaborations.

Discussions on developing data hubs, cores for implementation and dissemination, and pathways for clinician engagement in research were central to these sessions.

Education and Workforce Development:

Identified the importance of integrating research into medical education and training for primary care providers.

Proposed new pipeline programs to ensure that research is a core component of primary care practice, similar to other specialties like oncology.

The necessity of cultivating a “culture of inquiry” within primary care to drive ongoing research and innovation was underscored.

Sustainability and Scalability of PBRNs:

Addressed the need for sustainable models that support continuous research efforts beyond individual projects.

Emphasized the importance of securing funding, providing protected research time for clinicians, and aligning with health system priorities to ensure PBRNs can thrive.

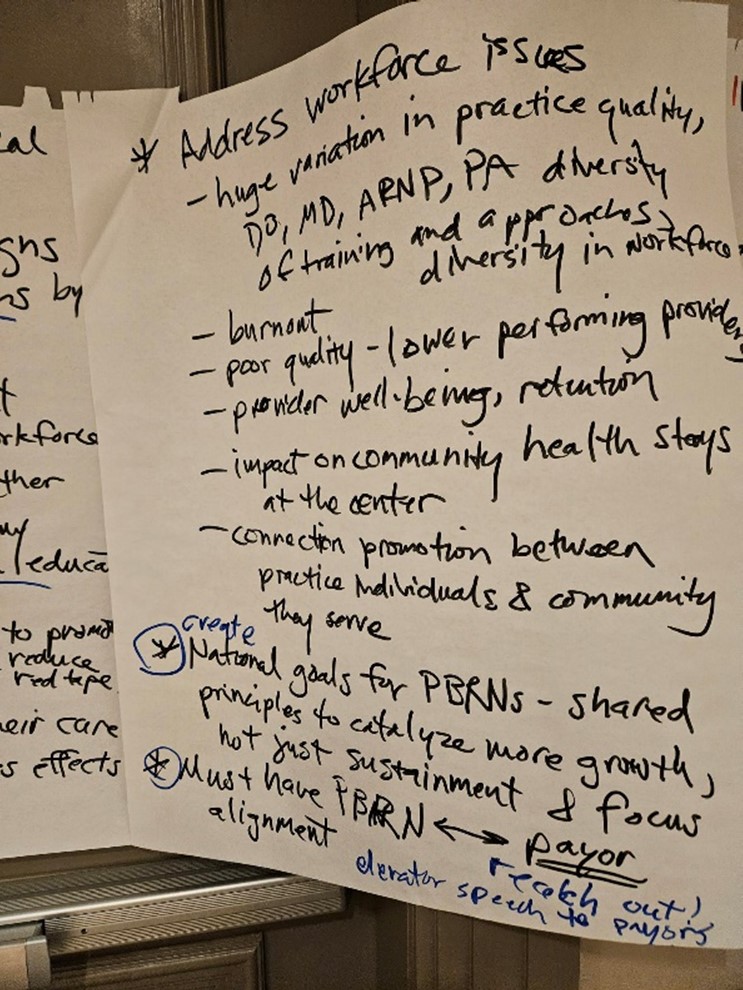

Highlighted challenges related to staffing, burnout, and the variability in practice quality, and proposed strategies to address these through systemic support and infrastructure development.

Leadership and Governance:

The summit discussed the need for strong leadership and governance structures to guide the growth and impact of PBRNs.

Encouraged the development of shared goals and principles at a national level to align PBRNs with broader healthcare objectives.

Explored the role of leadership in fostering trust, collaboration, and effective communication across PBRNs and with external stakeholders.

Recommendations

Enhancing Infrastructure:

Invest in developing and maintaining robust infrastructures such as data hubs and Centers of Excellence to support PBRN activities.

Create sustainable models that include ongoing support for practices, staff, and researchers, not just project-based funding.

Fostering Collaboration:

Strengthen partnerships between academia, healthcare systems, and community organizations to enhance the reach and impact of PBRNs.

Encourage interdisciplinary collaboration and engagement with diverse stakeholders to address complex healthcare challenges.

Promoting Education and Workforce Development:

Integrate research into the core curriculum of medical education, particularly in primary care disciplines.

Develop pipeline programs that prepare and encourage primary care providers to participate in research, with adequate support and resources.

Sustaining PBRNs:

Develop strategies to secure long-term funding, including negotiating for research-specific revenue streams within healthcare systems.

Address workforce issues by ensuring adequate staffing, reducing burnout, and improving the quality of care through continuous professional development and support.

Strengthening Leadership:

Establish clear leadership structures within PBRNs that promote shared vision, accountability, and the translation of research into practice.

Advocate for national policies and frameworks that support PBRNs and align them with healthcare system priorities.

This summary encapsulates the key discussions, themes, and recommendations from the Starfield VI Summit, focusing on how PBRNs can be leveraged to advance primary care, address health equity, and build a sustainable research ecosystem.

Summary

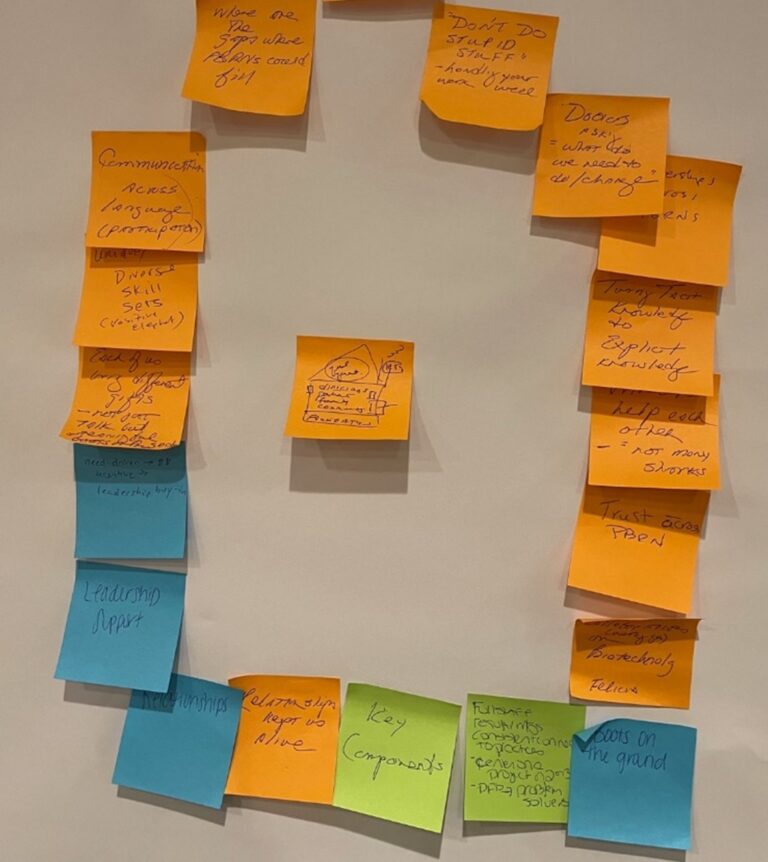

Dream – Sharing of small group visions for the future

Shared creative visuals, metaphors

The following emerged from collaborative Appreciative Inquiry groups.

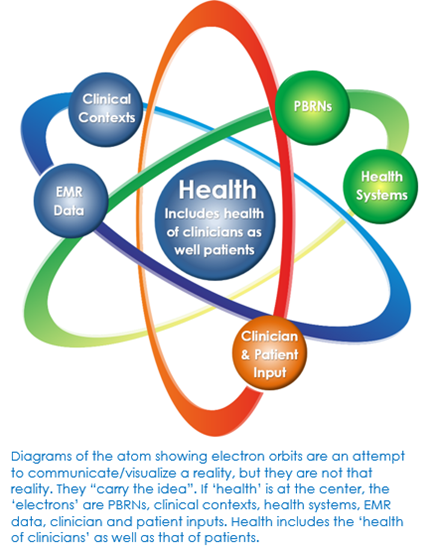

“Health Atom” Infrastructure/Bridges

PBRN infrastructure deals with clinical data, the voice of the marginalized/those who experience inequity, and what all that means for each clinic in a ‘health system’

We are building bridges that connect fertile academic/research/industry partnerships to fertile PBRN/practice contexts. The bridge is a ‘liminal (transitional) space’ where the ‘good stuff’ happens. We have a stock of wisdom/relationships in communities/clinics who have the ‘map’ to the right questions. The liminal space creates data and connects it to meaning. It spans boundaries. By recognizing and receiving and honoring what each of us contributes, we create virtuous cycles, that contribute to systemic change.

There are lots of destinations. Our bridges are like the stairs at Hogwarts that magically move and connect to others’.

The bridges are also like old medieval bridges that had businesses ON them.

Traffic managers across the bridges are study sections.

“Health Atom” Infrastructure/Bridges

PBRN infrastructure deals with clinical data, the voice of the marginalized/those who experience inequity, and what all that means for each clinic in a ‘health system’

We are building bridges that connect fertile academic/research/industry partnerships to fertile PBRN/practice contexts. The bridge is a ‘liminal (transitional) space’ where the ‘good stuff’ happens. We have a stock of wisdom/relationships in communities/clinics who have the ‘map’ to the right questions. The liminal space creates data and connects it to meaning. It spans boundaries. By recognizing and receiving and honoring what each of us contributes, we create virtuous cycles, that contribute to systemic change.

There are lots of destinations. Our bridges are like the stairs at Hogwarts that magically move and connect to others’.

The bridges are also like old medieval bridges that had businesses ON them.

Traffic managers across the bridges are study sections.

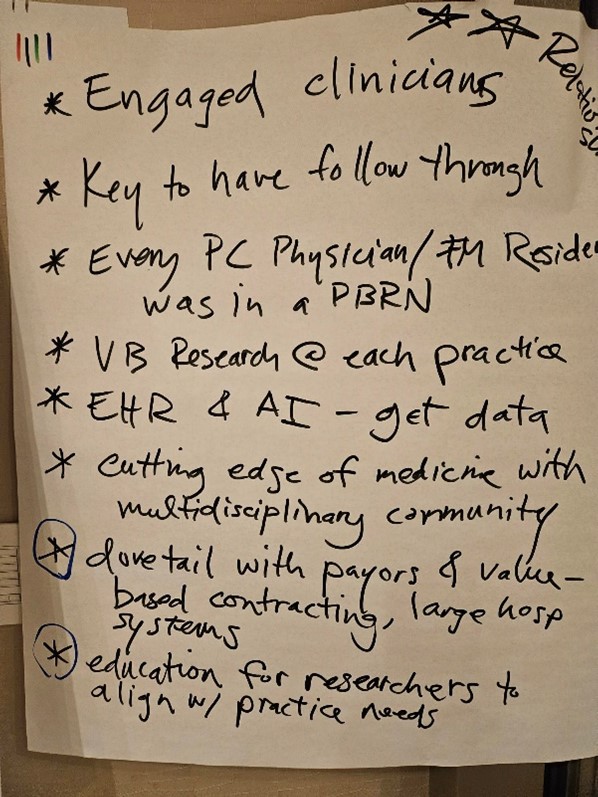

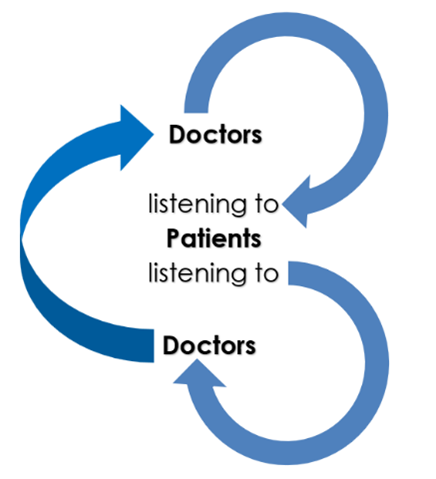

Engagement

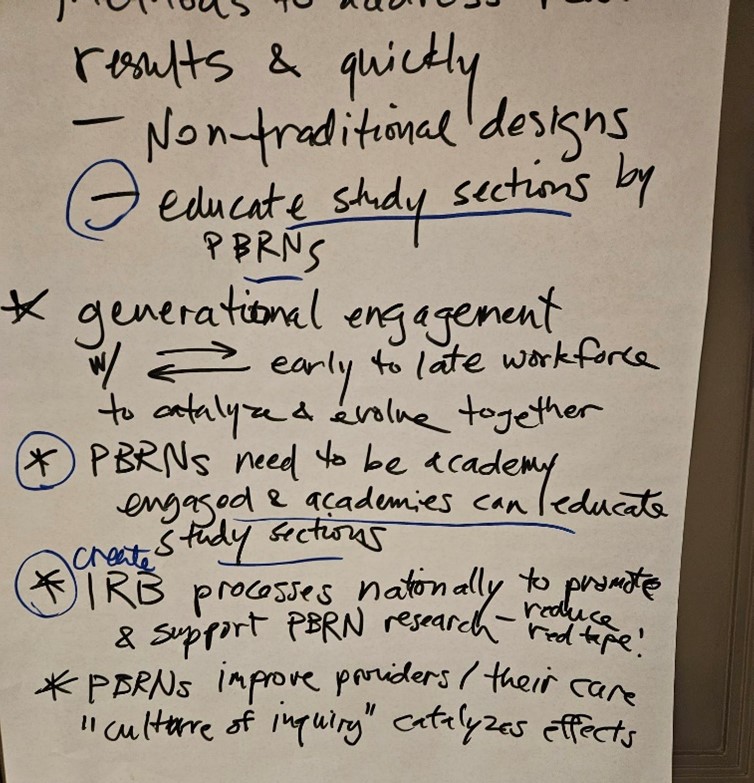

Engagement with clinicians across different systems, residencies, practice/clinics (the bridges) – are value-based, increasingl use AI, are EMR informed, multi-disciplinary, multi-sectoral, integrated into medical education, use non-traditional designs, educate funders, catalyze change

Engagement of the Academy (AAFP) is needed

Relationships matter

CTSAs are supporting some PBRNs, i.e. some CTSAs support some PBRNs

Goals

A goal is to improve providers’ care such that it embraces a ‘culture of inquiry’ to support research that addresses workforce issues, diversity in practice (staff and patient populations), burnout, quality assurance (bringing up the ‘low end’), and includes community-patient involvement.

Nationally, this will lead to shared goals/principles that will take us ‘over the top’ in terms of better alignment with government funders i.e. expansion of loan forgiveness; and payors i.e. better reimbursement. Common ground makes us collaborators not adversaries.

Shared interest, needs and successes

PBRNs need shared researcher interest, clinician interest, and patient interest.

Some PBRNs get ideas from “sentinel” clinicians and staff – folks in the practice that see something and bring it to the group. Many studies derive directly from clinical observations in the practice and community.

PBRNs need folks that wear “2-hats” i.e. have multiple roles such as a primary care clinician and who also performs research and/or is part of an academic setting. People and teams produce ideas!

Flexibility is important as proposals do not include definitive methods.

Reviewers with experience and understanding of PBRN research are needed, as they differ from other university academic researchers.

PBRNs are more successful when they have interim, interstitial, and ongoing support (support for staff, care and feeding of practices, developing ideas and projects), and not just project support.

PBRNs need fertile communities and practices

PBRNs need fertile academic institutions.

PBRN positioning

Unicorns – PBRNs are magically positioned to help bend the ‘arc of history’ towards equity but need better infrastructure and resources.

Sleeping Giant of primary care wisdom/knowledge/expertise both in clinicians and the communities in which practices are situated to care for THEIR patients with ‘boots on the ground’

Pipeline programs

New pipeline programs that propel, cultivate, and enable learners to take the ‘next step’ – changing the mentality so that there is NO QUESTION whether you as a learner/incoming provider will be involved in primary care research. Learners will see us ‘having fun doing research’ but also demand bandwidth to participate that is included in employment contract, e.g. in some specialties such as oncology, EVERY provider sees it as their duty and part-and-parcel of practice to be involved in research. This is not the current state of primary care. Primary care research must be ‘baked in” to every residency and department. “Transmogrify” residency research practices, require all Family Medicine residents to be members of NAPCRG, to participate in a PBRN project, create a movement that is a gateway to research e.g. “we are doing a survey together”

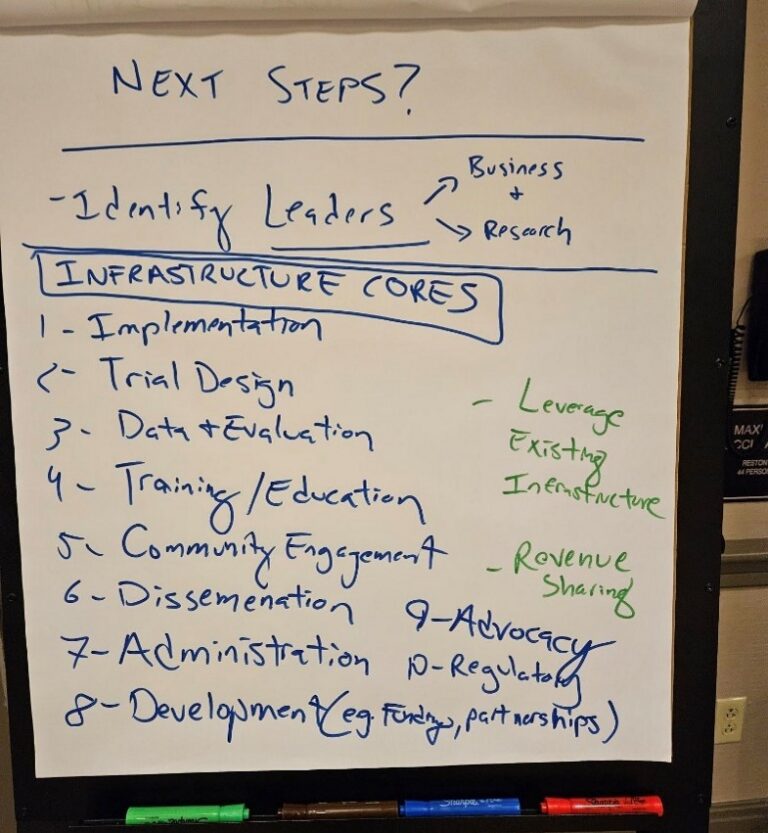

Design

Same small groups work to start planning instrumentally first steps to make their emerging visions for the future of PBRNs a reality

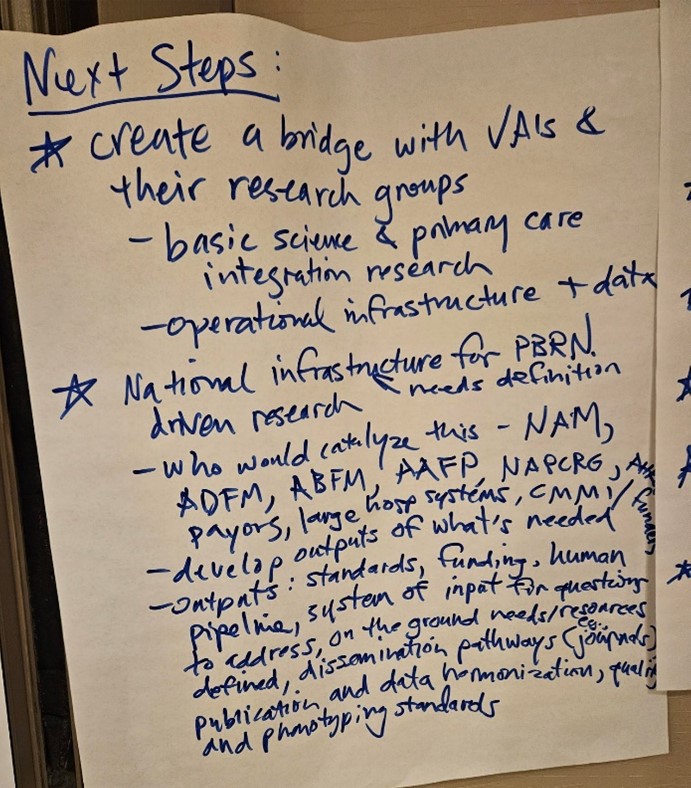

Next steps to ‘build the house’ (infrastructure group) – not just a single “mega-structure” but a collection of ‘inter-connected’ houses with a common space for interaction.

NIH-funded Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Research

Build partnerships that will be able to respond to funding announcements to improve healthcare policy- leverage the Center to create new jobs that the community values

Include FQHCs

Repository of clinical/EMR data across populations/systems e.g. data hub with agreements with HIE entities

Implementation and Dissemination Core- Clinical PBRN outcomes research, speed-up getting effective interventions in to practice

Data analysis core – use or develop methodologies that leverage the PBRN infrastructure and data opportunities

Administrative core – institutional commitment to accountability/support the Center e.g. advocate internally in organization for a wider vision of care; negotiate partial return of F&A to the Center of Excellence to support infrastructure; fund 10% of faculty time to do research for 3 years in “sentinel practices” where all docs have designated, protected research time, and all practice staff are recruited/trained to participate. Use each person at the upper limit of their scope of work. Negotiate buy-in from health system managers on the value proposition of the Center (how does what we produce by doing this benefit the organization financially); negotiate for research “RVUs”

Training Core for Practice-based research: educate Family docs in integration of research culture into the “job of doctoring”; develop ‘toolkits’ for medical students, residents, fellows relevant to PBRN research

Distinctive methodologies – that relate to the CASFM working group methodologies

For example, that use patient advisory boards in response to NAPCRG “Responsible Research in Communities” policy, that study the effectiveness of practice facilitators, define standards for relationships with CTSA or a larger research entity e.g. how PBRNs can best collaborate with CTSAs so that PBRNs are not dis-enfranchised or ghettoized.

Use a model that ties financial revenue from research to the clinical institution eg. Using the NIH Cancer Center model for cancer studies e.g. quality incentives that generate income for the primary care clinic in which the research takes place and produce infrastructural support between projects e.g. “support the animals” model (like animal researchers have in place between projects)

Connect to other organizations doing similar work at NIH e.g. NCI, NCATs/AHRQ/Common Fund activities may provide more/future funding; American Association of Nurse Practitioners; American Osteopathic Assn., American Association of Physician Assistants.

Until this is prioritized/funded, health systems will always cut out pieces of research infrastructure when funding is tight OR attempt to co-opt it for other non-research purposes

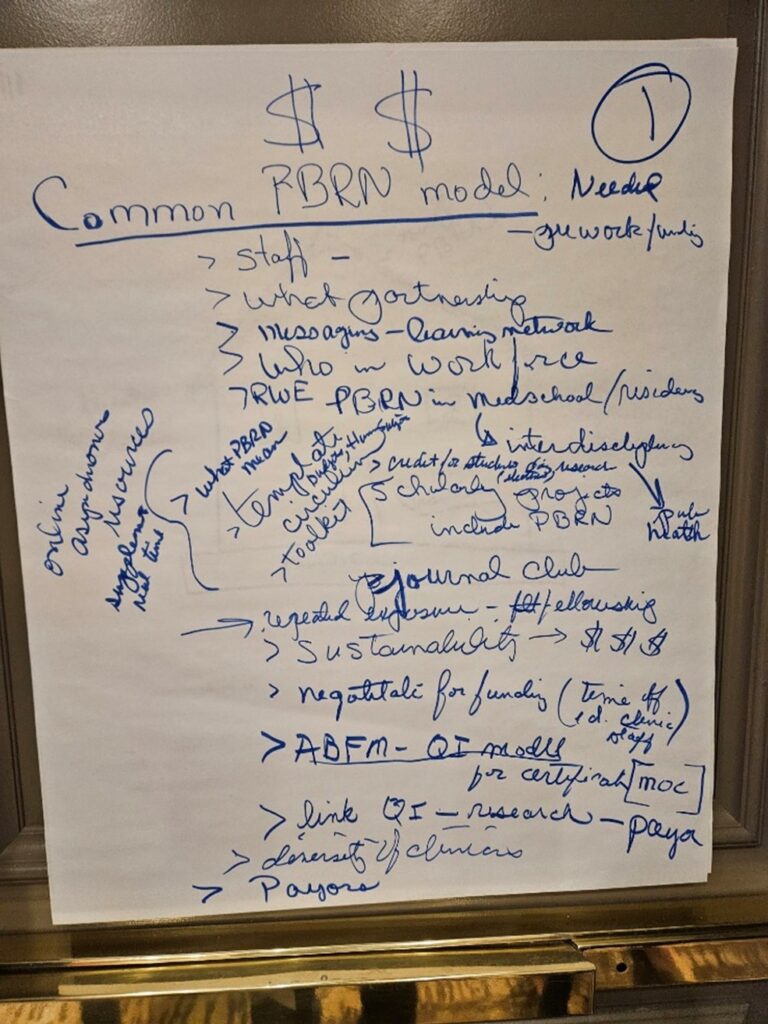

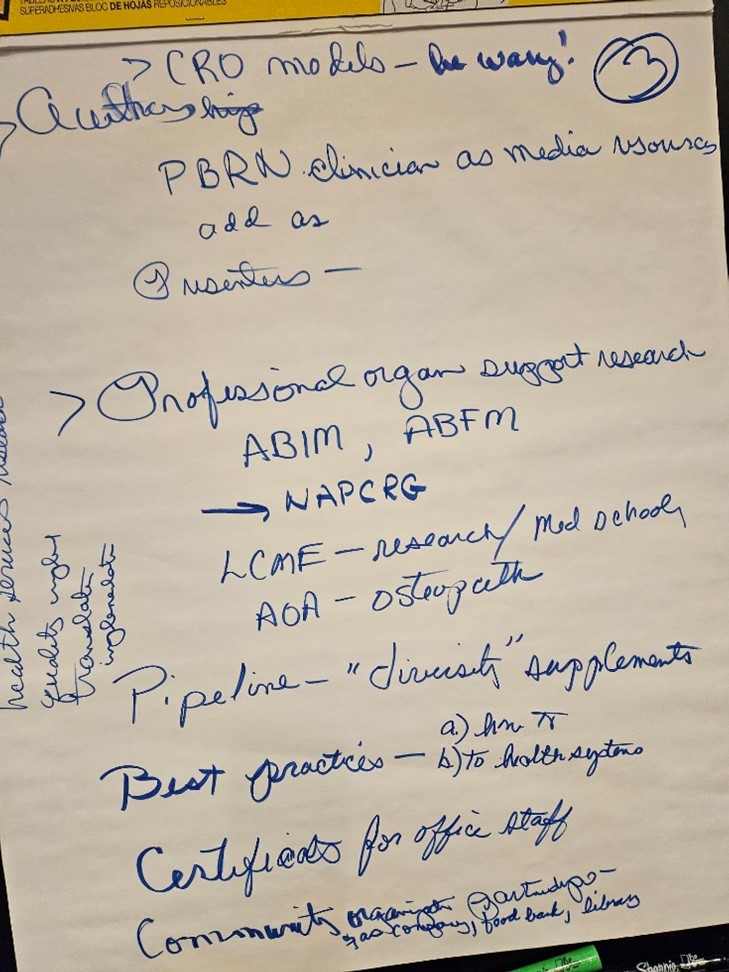

Consolidated Small Group Design Working Session (3 groups)

Build off momentum from smaller group discussions. Refine Design Plan to establish realistic, actionable steps toward implementing the Dream.

Small groups join to work on next steps around 3 topics – 2 groups per topic:

Infrastructure

Clinician & primary care researcher partnerships

Environmental opportunities for advancing PBRN research

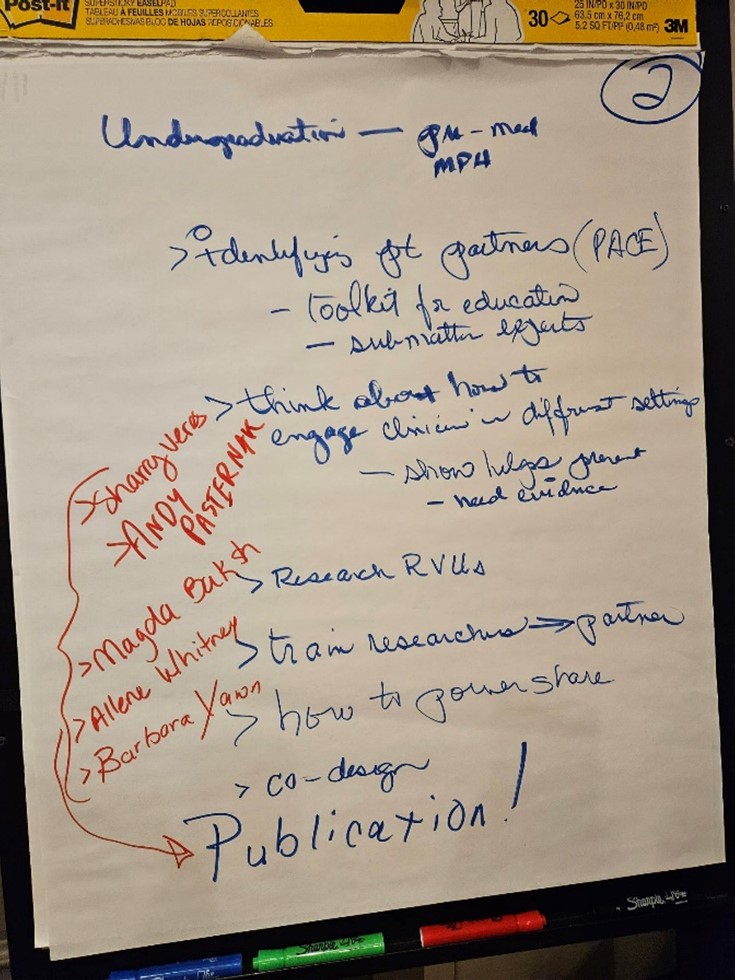

Undergraduates (pre-med; MPH)

Identify patient partners through PaCE

Provide a toolkit for education

Subject matter experts

Think about how to engage clinicians in different settings. Show _____ – need evidence.

Research RVUs

Train researchers ® partners

How to ___ share

C0-design

Publication!.

Documents

| Eastern Time | Topic |

|---|---|

| 9:00-9:15 |

Welcome (Wilson Pace) • Thoughts from the American Board of Family Medicine – Warren Newton |

| 35 minutes |

Kickoff Appreciative Inquiry (Kurt Stange) • Why I’m not a keynote speaker: personal history, challenges, current opportunity for PBRNs (20 min) • Discovery: paired reflect & share on peak experience re PBRN impact on new knowledge for health & equity. (12 min) • Shout-out and set up of small group Dream activity (3 min) |

| 55 minutes |

Sharing the Dream (Kurt Stange) • Groups of 6-8 use posterboard, crayons, creative materials to envision, at the level of metaphor & story: PBRNs in this moment of opportunity to address health, equity & primary care workforce • What would PBRNs look and feel like if they were about those peak experiences we just shared? |

| 10:45-11:00 | Break |

| 30 minutes |

Dream – Sharing of small group visions for the future • Share your creative visuals, metaphors |

| 60 minutes |

Design (Kurt Stange) Same small groups work to start planning instrumental first steps to make their emerging visions for the future of PBRNs a reality |

| 12:30-1:30 |

Lunch (Dream visuals posted for everyone to look at) • 12:45-1:15: Lunch speaker: Kevin Peterson from American Diabetes Association |

| 75 minutes |

Consolidated Small Group Design Working Session (3 groups) • Build off momentum from smaller group discussions. Refine Design Plan to establish realistic, actionable steps toward implementing the Dream. • Small groups join to work on next steps around 3 topics – 2 groups per topic: – Infrastructure – Clinician & primary care researcher partnerships – Environmental opportunities for advancing PBRN research |

| 2:45-3:00 | Break and CTR members join |

| 45 minutes |

Report Outs (Jack Westfall) • Three groups report on their Design Plans to the whole group and CTR members. |

| 45 minutes |

Full group discussion Opportunities and how everyone would like to contribute |

| 15–30 minutes |

Preliminary Synthesis from the day (Kurt Stange) Wrap up / Next steps (Wilson Pace, Jack Westfall, Joe LeMaster, Christina Hester) |

Preliminary Synthesis from the day & Wrap up/Next steps

The Starfield Summit VI focused on leveraging Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) to advance primary care, particularly in addressing health equity, improving infrastructure, fostering collaboration, and ensuring sustainability.

Major Themes

Health Equity and Workforce Challenges:

PBRNs are seen as crucial in addressing health disparities and strengthening the primary care workforce.

Discussions emphasized the need for PBRNs to engage with marginalized communities and contribute to more equitable healthcare outcomes.

Building and Strengthening Infrastructure:

A significant focus was on developing robust infrastructure, such as creating Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Research.

The need for sustainable models, including ongoing support for research and practices, was highlighted.

Proposals included establishing data hubs, cores for implementation and dissemination, and ensuring protected research time for clinicians.

Collaboration and Partnerships:

Emphasis on building partnerships between academic institutions, healthcare systems, and community organizations.

PBRNs were encouraged to act as bridges, connecting different stakeholders to address complex healthcare challenges.

Education and Pipeline Development:

Integration of research into the core curriculum of medical education, particularly for primary care, was recommended.

New pipeline programs are needed to ensure that research becomes a fundamental aspect of primary care practice.

Sustainability of PBRNs:

Discussions on securing long-term funding and aligning with health system priorities were central to ensuring the sustainability of PBRNs.

Addressing challenges like staffing, burnout, and variability in practice quality was deemed essential for the success of PBRNs.

Leadership and Governance:

Strong leadership and governance structures are required to guide PBRNs’ growth and impact.

Developing shared national goals and principles for PBRNs to align with broader healthcare objectives was suggested.

Key Recommendations

Enhance Infrastructure:

Invest in and maintain robust infrastructures, such as data hubs and Centers of Excellence, to support PBRN activities.

Foster Collaboration:

Strengthen partnerships between academia, healthcare systems, and community organizations.

Promote Education:

Integrate research into medical education and develop programs that encourage participation in primary care research.

Ensure Sustainability:

Develop sustainable models for PBRNs, including securing long-term funding and providing ongoing support for practices and research.

Strengthen Leadership:

Establish leadership structures within PBRNs that promote shared vision and accountability.

Additional ‘parked’ issues

Evening discussion with non-research primary care docs: Frontline doctors are suffering after the pandemic. The turnover of staff is very high a) everyone is new from nurses to receptionists, b) all are inexperienced and often “low functioning” c) there is likely to be more turnover during the coming few years as staff retire/change jobs. If we don’t provide practice facilitators for the practice, don’t expect that they will do much.

Doctors are being paid by ACOs and Advantage plans a) poorly, as in less than when they were in fee-for-service practices and b) much later than when services were provided, i.e. 12-18 months. Yet they must do it b/c the macra payments etc. would otherwise drive them out of business within 5 years.

Leveraging Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) to Advance Primary Care: Key Themes and Recommendations

Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) play a crucial role in advancing primary care by bridging the gap between clinical practice and research. These networks, composed of primary care practices, are designed to improve healthcare quality, equity, and effectiveness through research conducted in real-world settings. The insights gathered from the Starfield Summit VI and extant literature provide a comprehensive understanding of the challenges, opportunities, and future directions for PBRNs.

Major Themes

Health Equity and Workforce Challenges

Starfield Summit VI Insights: The summit highlighted the importance of PBRNs in addressing health disparities, particularly in marginalized communities. PBRNs are seen as vehicles for engaging these communities and driving equity in health outcomes by integrating diverse voices and experiences into research.

Literature Context: According to Fagnan et al. (2010), PBRNs are uniquely positioned to address health disparities by conducting community-based research that reflects the needs and experiences of underserved populations. They provide a platform for translating research findings into practice in a way that directly benefits these communities .

Building and Strengthening Infrastructure

Starfield Summit VI Insights: A key focus was on developing robust infrastructures, such as Centers of Excellence, that support the sustainability and growth of PBRNs. These infrastructures include data hubs, implementation and dissemination cores, and protected research time for clinicians.

Literature Context: Infrastructure is critical for the sustainability of PBRNs. Peterson et al. (2012) argue that the success of PBRNs depends heavily on the establishment of solid infrastructural support, including dedicated funding, data management systems, and administrative backing. Without these, PBRNs struggle to maintain momentum and impact .

Collaboration and Partnerships

Starfield Summit VI Insights: Collaboration was emphasized as essential for the success of PBRNs. Building partnerships between academic institutions, healthcare systems, and community organizations enables PBRNs to address complex healthcare challenges more effectively.

Literature Context: Green and Hickner (2006) suggest that the collaborative nature of PBRNs allows them to tackle broad, multifaceted issues in primary care. These collaborations bring together diverse expertise and resources, leading to more comprehensive and impactful research outcomes .

Education and Pipeline Development

Starfield Summit VI Insights: Integrating research into the core curriculum of medical education, particularly in primary care, was recommended to ensure a continuous pipeline of clinicians who are engaged in research.

Literature Context: The integration of research into medical education is vital for the future of PBRNs. Nutting et al. (2009) highlight that exposing medical students and residents to PBRNs early in their training fosters a culture of inquiry and prepares the next generation of clinicians to contribute to practice-based research .

Sustainability and Scalability of PBRNs

Starfield Summit VI Insights: Ensuring the sustainability of PBRNs requires securing long-term funding, providing ongoing support for practices, and aligning with health system priorities. Addressing issues like staffing, burnout, and variability in practice quality is crucial for sustaining PBRNs.

Literature Context: Sustaining PBRNs is a persistent challenge. According to Williams et al. (2010), long-term sustainability depends on diversifying funding sources, fostering institutional support, and ensuring that PBRNs are integrated into broader healthcare initiatives .

Leadership and Governance

Starfield Summit VI Insights: Strong leadership and governance structures are required to guide the growth and impact of PBRNs. Developing shared goals and principles at a national level can help align PBRNs with broader healthcare objectives.

Literature Context: Effective leadership is critical for the success of PBRNs. Mold and Peterson (2005) argue that PBRNs require leaders who can navigate the complex landscape of primary care research, advocate for necessary resources, and foster a collaborative and innovative research environment.

Key Recommendations

Enhance Infrastructure

Invest in the development of robust infrastructures, such as Centers of Excellence and data hubs, to support PBRN activities and ensure their sustainability.

Ensure that PBRNs have the necessary resources, including protected research time for clinicians and administrative support, to sustain long-term projects.

Foster Collaboration

Strengthen partnerships between academic institutions, healthcare systems, and community organizations to enhance the reach and impact of PBRNs.

Encourage interdisciplinary collaboration to address the complex challenges faced in primary care.

Promote Education and Workforce Development

Integrate research into the medical education curriculum, particularly in primary care, to ensure that future clinicians are equipped to engage in research.

Develop pipeline programs that provide ongoing support and mentorship for primary care providers involved in research.

Ensure Sustainability

Develop sustainable models for PBRNs that include diversified funding sources, long-term institutional support, and alignment with health system priorities.

Address workforce challenges by ensuring adequate staffing, reducing burnout, and improving the quality of care through continuous professional development.

Strengthen Leadership and Governance

Establish clear leadership structures within PBRNs that promote a shared vision, accountability, and the translation of research into practice.

Advocate for national policies and frameworks that support PBRNs and align them with broader healthcare objectives.

Conclusion

PBRNs are instrumental in advancing primary care by fostering research that is directly applicable to clinical practice. By addressing health equity, building strong infrastructures, promoting collaboration, and ensuring sustainability, PBRNs can continue to contribute significantly to improving healthcare outcomes. The recommendations provided aim to support the ongoing development and impact of PBRNs in a rapidly evolving healthcare landscape.

References

Fagnan, L. J., Davis, M., Deyo, R. A., Werner, J. J., & Stange, K. C. (2010). Linking practice-based research networks and clinical and translational science awards: new opportunities for community engagement by academic health centers. Academic Medicine, 85(3), 476-483.

Peterson, K. A., Lipman, P. D., & Lange, C. J. (2012). Building the infrastructure to improve the quality of care: practice-based research networks (PBRNs) in the United States. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 25(5), 565-571.

Green, L. A., & Hickner, J. (2006). A short history of primary care practice-based research networks: From concept to essential research laboratories. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 19(1), 1-10.

Nutting, P. A., Beasley, J. W., Werner, J. J., & Stange, K. C. (2009). Practice-based research networks answer primary care questions. Journal of the American Medical Association, 301(11), 1114-1116.

Williams, R. L., Rhyne, R. L., & Fink, R. L. (2010). Sustainable practice-based research networks: the lifeblood of primary care research. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 23(4), 432-438.

Mold, J. W., & Peterson, K. A. (2005). Primary care practice-based research networks: working at the interface between research and quality improvement. Annals of Family Medicine, 3(Suppl 1), S12-S20.

Annotated Bibliography on Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) in North America

1. Fagnan, L. J., Davis, M., Deyo, R. A., Werner, J. J., & Stange, K. C. (2010). Linking practice-based research networks and clinical and translational science awards: new opportunities for community engagement by academic health centers. Academic Medicine, 85(3), 476-483.

Annotation:

This paper discusses the integration of PBRNs with Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSAs) to enhance community engagement in research. The authors argue that linking PBRNs with CTSAs can bridge gaps between academic research and community practice, facilitating more relevant and impactful health research. This connection not only enhances the research capacity of PBRNs but also aligns their activities with national health priorities. The paper is a significant contribution to understanding how PBRNs can be leveraged to foster community-engaged research within academic health centers.

2. Green, L. A., & Hickner, J. (2006). A short history of primary care practice-based research networks: From concept to essential research laboratories. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 19(1), 1-10.

Annotation:

Green and Hickner provide a historical overview of PBRNs, detailing their evolution from a conceptual framework to becoming essential research laboratories for primary care. The paper emphasizes the role of PBRNs in generating evidence that is directly applicable to clinical practice, particularly in real-world settings. The authors highlight the unique contributions of PBRNs to the primary care research landscape, including their ability to conduct studies that are relevant to the needs of everyday clinical practice. This work is foundational for understanding the development and significance of PBRNs in North America.

3. Mold, J. W., & Peterson, K. A. (2005). Primary care practice-based research networks: working at the interface between research and quality improvement. Annals of Family Medicine, 3(Suppl 1), S12-S20.

Annotation:

This paper explores the dual role of PBRNs in conducting research and driving quality improvement in primary care settings. Mold and Peterson argue that PBRNs are uniquely positioned to integrate research findings into clinical practice, thus improving the quality of care provided to patients. The paper discusses various strategies for sustaining PBRNs, including the importance of leadership, collaboration, and funding. This article is particularly useful for understanding how PBRNs operate at the intersection of research and practice, contributing to both scientific knowledge and the enhancement of healthcare quality.

4. Nutting, P. A., Beasley, J. W., Werner, J. J., & Stange, K. C. (2009). Practice-based research networks answer primary care questions. Journal of the American Medical Association, 301(11), 1114-1116.

Annotation:

Nutting et al. focus on the role of PBRNs in answering key questions in primary care through practice-based research. The paper discusses the types of research questions that PBRNs are well-suited to address and the methodologies they employ. The authors highlight the importance of PBRNs in filling gaps in primary care research, particularly in areas that are underexplored by traditional research methods. This article is essential for understanding how PBRNs contribute to evidence-based practice in primary care.

5. Peterson, K. A., Lipman, P. D., & Lange, C. J. (2012). Building the infrastructure to improve the quality of care: practice-based research networks (PBRNs) in the United States. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 25(5), 565-571.

Annotation:

This article examines the infrastructural needs of PBRNs to improve the quality of care in the United States. Peterson and colleagues discuss the critical components of a successful PBRN infrastructure, including data management systems, administrative support, and sustainable funding models. The paper provides insights into the challenges faced by PBRNs in maintaining robust research activities and offers recommendations for building and sustaining these networks. This work is valuable for anyone looking to understand the practical aspects of establishing and maintaining a PBRN.

6. Williams, R. L., Rhyne, R. L., & Fink, R. L. (2010). Sustainable practice-based research networks: the lifeblood of primary care research. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 23(4), 432-438.

Annotation:

Williams et al. explore the sustainability of PBRNs, identifying them as the “lifeblood” of primary care research. The paper discusses the factors that contribute to the long-term viability of PBRNs, such as securing diverse funding sources, fostering institutional support, and ensuring that research activities align with the needs of primary care providers. The authors also emphasize the importance of integrating PBRNs into broader healthcare initiatives to enhance their impact and sustainability. This article is essential for understanding the challenges and strategies associated with sustaining PBRNs over time.

7. Westfall, J. M., Mold, J., & Fagnan, L. (2007). Practice-based research—“Blue highways” on the NIH roadmap. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297(4), 403-406.

Annotation:

This seminal paper introduces the concept of PBRNs as the “blue highways” on the National Institutes of Health (NIH) roadmap, emphasizing their role in translating research into practice. Westfall, Mold, and Fagnan argue that PBRNs provide a critical pathway for disseminating and implementing research findings in real-world clinical settings. The paper advocates for increased recognition and support of PBRNs within the NIH framework, highlighting their potential to bridge the gap between research and practice. This article is a key reference for understanding the strategic importance of PBRNs in the broader context of health research and policy.

8. Pace, W. D., Fagnan, L. J., & West, D. R. (2011). The evolving role of practice-based research networks in facilitating translational research. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 24(5), 489-492.

Annotation:

This paper discusses the evolving role of PBRNs in facilitating translational research, which involves turning scientific discoveries into practical applications in healthcare. Pace and colleagues highlight the ways in which PBRNs are uniquely equipped to bridge the gap between bench research and bedside practice. The paper also explores the challenges PBRNs face in this role, including the need for robust infrastructure and sustainable funding. This article is valuable for understanding how PBRNs contribute to the translation of research into practice.

9. Tierney, W. M., Oppenheimer, C. C., Hudson, B. L., Benz, J., Finn, A., Hickner, J. M., … & Smith, M. A. (2007). A national survey of primary care practice-based research networks. Annals of Family Medicine, 5(3), 242-250.

Annotation:

Tierney et al. conducted a national survey of PBRNs to assess their characteristics, challenges, and successes. The study provides a comprehensive overview of the state of PBRNs across the United States, including information on their organizational structures, research activities, and funding sources. The paper also identifies key barriers to PBRN sustainability, such as funding instability and administrative burden. This article is a crucial resource for understanding the landscape of PBRNs in the U.S. and the factors that influence their success.

10. Green, L. A., White, L. L., Barry, H. C., Nease, D. E., & Hudson, B. L. (2005). Infrastructure requirements for practice-based research networks. The Annals of Family Medicine, 3(Suppl 1), S5-S11.

Annotation:

This paper outlines the infrastructure requirements for establishing and maintaining effective PBRNs. Green and colleagues discuss the essential components of a PBRN infrastructure, including data management, communication systems, and administrative support. The authors also emphasize the importance of securing stable funding and fostering collaborative relationships with academic and community partners. This work is particularly useful for those involved in the planning and development of PBRNs, offering practical guidance on building the necessary infrastructure for successful research activities.

This annotated bibliography provides a comprehensive overview of key literature on Practice-Based Research Networks in North America, highlighting their evolution, challenges, and contributions to primary care research. Each entry is selected for its relevance to understanding the development, operation, and impact of PBRNs, offering insights into their role in bridging the gap between research and clinical practice.

Working Group

Environment/Policy work group

The report examines the current environment for Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) as explored by the attendees of the Starfield Summit IV. It focuses on actionable recommendations to improve the ability of PBRNs to serve their core function within primary care research.

Background

Primary Care Importance: A well-functioning primary care system is the foundation of highly functioning health care systems.

Underfunding: The US primary care system is underfunded compared to other parts of the health care system, including health-related research funding.

Role of PBRNs: PBRNs are crucial for advancing knowledge within primary care through ongoing research, dissemination, and implementation.

Summit Overview

Assumptions: PBRNs are a core research approach within primary care but are struggling to survive and serve as main drivers of innovation.

Attendees: Included individuals with US and international PBRN experience, Family Medicine professional organizations, and major health care and services funding organizations.

Sponsors: DARTNet Institute, North American Primary Care Research Group, American Diabetes Association, American Board of Family Medicine, and American Academy of Family Physicians.

Format: One-day, invitation-only, in-person meeting with short presentations and small group work focused on appreciative inquiry.

Main Constructs and Subcomponents

Location-Based Environments:

Communities: Interested communities, community stewardship, and responsible research.

Clinical Organizations: Support at leadership level, demonstrating benefit.

Clinical Care Sites: Prepared clinicians and staff, network support and respect, diversity of clinical sites and people cared for.

PBRN Home: Impact of academic, professional society, health care organization, and standalone PBRN homes.

Researcher Pipeline:

MD or MD/PhD: Clinician researchers.

PhD: Research-focused individuals.

Early Learners: Medical, psychology, pharmacy students, and residents.

RapSDI Model: Reproduced and supported by other PBRNs.

Funder Environment:

Expanded Role: Role of PBRN research in specialty/disease-oriented funding environments.

Funding Sources: Federal (NIH, AHRQ, CDC, FDA, HRSA, NSA), quasi-federal (PCORI), foundations, advocacy groups, and private industry.

Reimbursement Systems:

Expanded Role: Role of PBRN research in specialty/disease-oriented funding environments.

Funding Sources: Federal (NIH, AHRQ, CDC, FDA, HRSA, NSA), quasi-federal (PCORI), foundations, advocacy groups, and private industry.

Infrastructure:

Critical Cores: Admin core, research core, unique methodologies, analytical core, data core, engagement core, training core.

New Funding Opportunities: NIH, advocacy organizations, novel foundations (e.g., Bezos).

Discussion

Environmental Constructs: Detailed examination of constructs and their subcomponents.

Staff Definition: Inclusion of all clinical site staff from front desk to clinic.

Learners: Importance of including medical students and other early learners in the research pipeline.

Conclusion

The report emphasizes the need for actionable recommendations to improve the environment in which PBRNs operate, ensuring their sustainability and effectiveness in advancing primary care research.

Infrastructure Working group

The meetings focused on the infrastructure needs for Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) and the practical steps to translate ideas into reality. The discussions highlighted the importance of sustainable infrastructure funding, practical steps to support PBRNs, and the evolving roles and missions of PBRNs.

Seven persons participated twice

Key Points Discussed

Infrastructure Funding:

Emphasis on the need for sustainable infrastructure funding for PBRNs.

Suggestions included developing relationships with national centers like NCI or CTSA to ensure recurring grant opportunities that include infrastructure costs.

Practical Steps:

Developing relationships with funding bodies and creating pilot funding mechanisms for new researchers.

Addressing the varying needs of PBRNs based on their size and affiliation.

Ensuring flexibility and innovation within PBRNs while maintaining their missions.

Supporting new PBRNs to emerge and grow.

Consortium Model:

Creating consortiums to handle infrastructure needs as a potential solution to support smaller PBRNs.

Consortiums could provide centralized functions like grant writing, IRB support, and other essential services.

Engagement and Participation:

Emphasizing the importance of engaging practices and maintaining relationships with them.

The need for face-to-face interactions to build trust and ensure successful participation in research studies.

Roles and Missions of PBRNs:

Adjusting the roles and missions of PBRNs to align with the new environment.

Considering PBRN leaders as business-like managers with managerial education.

Balancing top-down and bottom-up management approaches.

Value Proposition:

Highlighting the value of PBRNs to institutions, including maintaining relationships with practices and supporting clinical training sites.

Emphasizing the importance of documenting and incorporating the indirect costs of PBRN work into organizational calculations.

Research Ready Practices:

Developing research-ready practices to streamline future collaborations.

Building base relationships and processes to reduce the lift for future projects.

Workforce Development:

Facilitating the development of clinical investigators who want to participate in research regularly.

Developing PBRN leaders who can run PBRNs effectively and engage practices in meaningful research.

Program-Based Support:

Advocating for program-based support rather than project-based funding to maintain infrastructure and institutional knowledge.

Ensuring that funding mechanisms account for the true expenses of PBRN-related work.

Participants were not interested to pursue the “funded Center grant” pathway, i.e. to specify details of an RFA for future promotion /use by AHRQ or NIH

Rather, they asserted and agreed that funding for PBRN infrastructure should be included, and required to be included in CTSAs, National Cancer Centers and other similar large institutional grants, such that the infrastructure is both invested in and maintained as a core “fixed cost”, similar to the fixed cost of maintaining laboratory facilities, rather than maintaining those human or other resources as part of “project funding” that must of necessity be repeatedly re-funded by the next project, or be at-risk of loss. This should be a requirement for renewal of CTSA and NCI Cancer institute funding.

Next Steps:

Summarizing notes and conversations from the sessions.

Sharing insights with other workgroups focused on environment and policy, and human resources and pipeline development.

Planning for a workshop at NAPCRG to report on the discussions and develop a comprehensive strategy to support PBRNs

Conclusion

The infrastructure working group meetings concluded with a plan to continue discussions and share insights across different workgroups. The ultimate goal is to develop a comprehensive strategy to support PBRNs and ensure their sustainability and growth.

Training/pipeline working group

The document outlines discussions from the Primary Care Research Workforce meeting held on September 20, 2024. The focus was on creating a pipeline for future researchers, defining roles, and advocating for primary care research.

Key Points Discussed

Research Impact and History:

Cataloging research that has changed practice.

Creating a public-facing document on the history of PBRNs and their importance.

Developing a list of 100 questions that can only be answered by family medicine research.

Advocacy and Communication:

Encouraging physicians to be involved in research rather than just consuming it.

Highlighting practice-changing research at conferences like NAPCRG.

Advocacy for smaller grants to support early-stage researchers.

Funding and Infrastructure:

Encouraging physicians to be involved in research rather than just consuming it.

Highlighting practice-changing research at conferences like NAPCRG.

Advocacy for smaller grants to support early-stage researchers.

Roles and Pathways:

Defining various roles for family physicians (FPs) in research, including question development, data collection, and logistical support.

Creating pathways for mid-career FPs to get involved in research.

Pairing residents and students with practicing clinicians who are involved in research.

Engagement and Readiness:

Conducting readiness assessments for new practices joining PBRNs.

Evaluating interests, knowledge, and capacity of practice staff.

Ensuring clinical and administrative teams are aligned for successful research participation.

Challenges and Solutions:

Addressing barriers to research participation, especially in rural health practices.

Articulating the “why” for FPs to engage in research, including monetary benefits, addressing burnout, and clinical inquisitiveness.

Communicating the benefits of research to leadership and clinicians.

Collaboration and Support:

Harnessing the power of academic medical centers (AMCs) to partner with practices.

Encouraging chairs to use their power to make space for primary care research.

Creating modules for Board certification to incentivize research participation.

Community and Education:

Engaging community members and boards of practices in research.

Developing research that can help with CME credits and Board certification.

Pairing medical students with researchers to foster interest in primary care research.

Conclusion

Engaging community members and boards of practices in research. Developing research that can help with CME credits and Board certification. Pairing medical students with researchers to foster interest in primary care research.

Integration of Practice-Based Research into Family Medicine and Primary Care Research

Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) have become a vital component of family medicine and primary care research, serving as a bridge between academic research and real-world clinical practice. Their integration into the broader field of primary care research has led to significant advancements in the quality, relevance, and applicability of research findings to everyday clinical settings.

Key Aspects of Integration

Real-World Relevance

Focus on Practicality: PBRNs conduct research in the environments where healthcare is actually delivered—clinics, practices, and communities. This focus ensures that the research questions are directly relevant to primary care practitioners and their patients, addressing the specific challenges they face.

Patient-Centered Research: By operating within the primary care setting, PBRNs emphasize patient-centered outcomes, aligning with the broader goals of family medicine to provide comprehensive, continuous, and coordinated care.

Collaboration Between Academics and Clinicians

Bridging the Gap: PBRNs facilitate collaboration between academic researchers and practicing clinicians. This partnership allows for the generation of research questions that are clinically relevant and the implementation of research findings in a way that is practical and feasible in everyday practice.

Mutual Benefit: Academic researchers gain access to real-world data and insights, while clinicians benefit from evidence-based tools and interventions that improve patient care. This symbiotic relationship enhances the overall quality of primary care research.

Quality Improvement and Implementation Science

Continuous Improvement: PBRNs play a crucial role in the integration of quality improvement initiatives within family medicine. Research conducted within PBRNs often leads to the development of best practices that are then disseminated and implemented across other practices, driving continuous improvement in care delivery.

Implementation Science: PBRNs are also central to the field of implementation science, which focuses on how best to integrate research findings into routine clinical practice. This is particularly important in primary care, where the translation of research into practice is often more challenging due to the variability of settings and patient populations.

Education and Training

Cultivating a Research Culture: PBRNs contribute to the education and training of the next generation of family physicians and primary care providers. By involving medical students, residents, and practicing clinicians in research, PBRNs foster a culture of inquiry and evidence-based practice within primary care.

Pipeline Development: PBRNs are instrumental in developing research pipelines within primary care, ensuring that new practitioners are equipped with the skills and knowledge necessary to engage in and apply research throughout their careers.

Health Equity and Community Engagement

Addressing Disparities: PBRNs are uniquely positioned to address health disparities by conducting research that is directly relevant to underserved and marginalized populations. By engaging with communities and tailoring research to local needs, PBRNs contribute to more equitable healthcare outcomes.

Community-Based Participatory Research: Many PBRNs adopt a community-based participatory research approach, actively involving patients and community members in the research process. This enhances the relevance and impact of the research, ensuring that it addresses the specific health concerns of the communities served.

Conclusion

Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) have become an integral part of the broader field of family medicine and primary care research. By bridging the gap between academic research and clinical practice, PBRNs ensure that research is relevant, practical, and directly applicable to the challenges faced by primary care providers. Through their focus on real-world settings, collaboration, quality improvement, education, and health equity, PBRNs enhance the overall quality and impact of primary care research, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes and more effective healthcare delivery.